Why Do Vacations Feel So Hard? Parenting, Transitions, and the "Capacity Gap"

If you're short on time: Feeling dread instead of excitement about family trips isn't a character flaw. It's your nervous system signaling it's near capacity. High-stress situations like vacations, holidays, and school breaks reveal the invisible gaps in how mental load gets distributed in your partnership. This post explains what's actually happening and offers practical steps for partnering through capacity differences without resentment.

You're planning a family trip. Maybe it's a holiday visit, a school break, or a long-awaited vacation. Your partner seems genuinely excited. You, however, feel a wave of dread.

As a Registered Clinical Counsellor and Occupational Therapist specializing in nervous system regulation and parental burnout, I've worked with hundreds of parents navigating this exact dynamic. The partner who carries more mental load during regular life often carries exponentially more during transitions, travel, and disruptions to routine. This isn't about being ungrateful or unable to relax. It's about nervous system capacity and how high-stress situations magnify existing imbalances in a partnership.

The Common Misunderstanding: "We're Both Tired"

Many couples frame capacity differences as a matter of effort or willingness. One partner might say, "I'm tired too," or "I offered to help, but you didn't ask." The other partner feels resentful, isolated, and increasingly depleted. Both feel misunderstood.

What's often missing from these conversations is an understanding of how nervous system capacity actually works. When one partner is already operating near their regulation limit during regular life, high-stress situations like travel don't just add more to their plate. They push that partner into survival mode, where even basic tasks feel overwhelming.

This cycle often starts long before the big event. As I discussed in my post on holiday burnout, seasonal demands stack on top of an already depleted baseline, slowly chipping away at your window of tolerance before you even leave the house.

This shows up during:

School breaks and holidays. Routine disappears. Kids are home more. Meal planning intensifies. The house becomes an all-day-buffet with snack plates littering every surface, unfinished art projects gathering dust and oscillation between screen time requests and complaints of being bored. Emotional regulation demands spike for everyone.

Travel and vacations. Packing, coordinating, timing naps, managing transitions, holding everyone's big emotions, meal planning with picky eaters, navigating unfamiliar environments. One partner is mentally three steps ahead at all times while the other is present in the moment.

Moving or major transitions. The parent carrying more mental load is coordinating logistics, managing everyone's emotions about the change, maintaining routines as much as possible, and trying to hold their own stress at the same time.

Illness or disruption. When a child is sick, when plans change suddenly, when something goes wrong, one partner typically absorbs the majority of the problem-solving, emotional regulation, and recalibration work.

The Exhaustion Olympics: When "We're Both Tired" Becomes a Competition

I see this dynamic constantly in my practice working with couples. It usually sounds like this:

Partner A: "I've been with the kids all day and I'm completely drained, I have nothing left to give."

Partner B: "Well, I've been in back-to-back meetings and stuck in traffic for two hours."

When we slip into the Exhaustion Olympics, we're inadvertently telling our partner: "My stress invalidates yours." From a nervous system perspective, this is a race to the bottom. When you feel you have to prove your exhaustion to earn rest, your body stays in a state of hypervigilance. You can't actually relax because you're busy building a case for why you deserve to.

Here's what's happening physiologically: both nervous systems are activated, both are seeking safety and relief, but instead of co-regulating, you're competing. Neither person gets what they actually need, which is acknowledgment and support.

The shift that changes everything: Two people can be at capacity at the same time. The goal isn't to decide who's more deserving of a break. It's to acknowledge that the system is overloaded and needs a collective strategy to bring the temperature down for both of you.

What's Actually Happening: Nervous System Capacity and the Mental Load

When we talk about "mental load," we're often describing the invisible work of anticipating needs, coordinating logistics, remembering details, and holding emotional space. This work requires significant cognitive and emotional energy. It also requires nervous system capacity.

Capacity is finite. Your nervous system has a limited amount of bandwidth for processing information, managing emotions, making decisions, and staying regulated. When that capacity is consistently taxed by carrying the mental load at home, there's less available for handling the additional demands of travel, disruption, or high-stress situations.

Think of your family as a single electrical circuit. If one part of the circuit is consistently pulling 90% of the power to keep the lights on, there's no surge protection left when a transition hits. The system overloads.

When we're in this state of chronic depletion, we often find ourselves reacting in ways that don't align with the parents we want to be. If you've found yourself snapping at your kids and feeling that immediate wave of shame, my guide on parent burnout and repair offers support for navigating those moments when you feel like you're losing it.

Dysregulation compounds. When your nervous system is already working hard to stay regulated during daily life, adding more stressors doesn't just increase the load linearly. It can push you into a state where your window of tolerance shrinks dramatically. Suddenly, small things feel big. Flexibility disappears. Irritability spikes. You're no longer just tired. You're dysregulated.

The body keeps score. Even if you're "managing" on the surface, your nervous system is tracking every micro-task, every emotional regulation moment, every decision you're holding. During high-stress times, this accumulated load catches up. You might find yourself snapping at your partner, feeling tearful over something minor, or experiencing physical symptoms like tension, fatigue, or difficulty sleeping.

Here's how this plays out: One partner craves structure and predictability and insists on arriving at the airport three hours early. The other partner is carrying the mental load for packing everyone's belongings, coordinating logistics, and managing the kids' emotions, and they're still stuffing items into suitcases at the last possible minute.

Neither person is wrong. One nervous system needs extra buffer time to feel safe. The other nervous system is so maxed out that tasks don't get done until the pressure of a deadline forces action. Without understanding what's happening beneath the surface, this becomes a recurring fight about "why can't you ever be ready on time?" and "why do you make us get there so early?"

From years of working with overwhelmed parents, I've seen a consistent pattern: the partner carrying more mental load isn't asking for their partner to "help more" in a vague sense. They're asking for their partner to share the invisible work of anticipating, coordinating, and emotionally holding the family system, especially during times when that work intensifies.

The Reframe: Different Capacity Isn't a Character Flaw

Here's what I want you to hear: if you're the partner who feels dread instead of excitement about family trips, you're not broken. You're not ungrateful. Your nervous system is doing exactly what nervous systems do when they're operating near capacity. It's protecting you by signaling, "This is going to be hard."

If you're the partner who doesn't automatically see all the invisible work that needs to happen, that's not a character flaw either. You likely weren't socialized to track and manage the same set of details, or your "radar" for these tasks has stayed dormant because the other partner has always handled them. You might have more nervous system capacity available because you're not carrying the same cognitive and emotional load during daily life.

The issue isn't who's "better" or "worse" at parenting. It's that high-stress situations reveal and magnify existing imbalances in how mental load is distributed. When routine disappears, the gaps become impossible to ignore.

This reframe matters because it shifts the conversation from blame to understanding. Instead of "Why can't you just relax?" or "Why don't you ask for help?", the question becomes: "How do we redistribute this work in a way that honors both of our capacity and keeps both of us out of survival mode?"

What This Looks Like in Real Life: Practical Steps for Partnering Through Capacity Differences

1. Name the Pattern Before the Stressor Hits

Don't wait until you're in the middle of a chaotic vacation to talk about capacity differences. Have the conversation during a calm moment.

Here's what this looks like in real life: One partner craves structure and predictability and wants to arrive at the airport three hours before the flight. The other partner is holding the mental load for the entire family and still finds themselves packing at the last minute. Neither person is wrong. One partner's nervous system needs extra time as a buffer against uncertainty. The other partner's nervous system is so overloaded that even "simple" tasks like packing feel impossible until the deadline forces action.

Without naming this pattern, you end up with resentment on both sides. The early-arrival partner feels anxious and dismissed. The last-minute partner feels criticized and ashamed.

Try: "I've noticed that during school breaks, I feel like I'm holding a lot more of the planning and emotional regulation work. Can we talk about how to share that differently this time?"

Or: "I know you need us to leave early for the airport, and I want to honor that. But I'm also noticing that I'm doing all the packing for everyone, which is why I'm always running late. Can we figure out how to redistribute the prep work so we can both get what we need?"

This isn't about criticizing your partner. It's about naming a pattern so you can both prepare and problem-solve together.

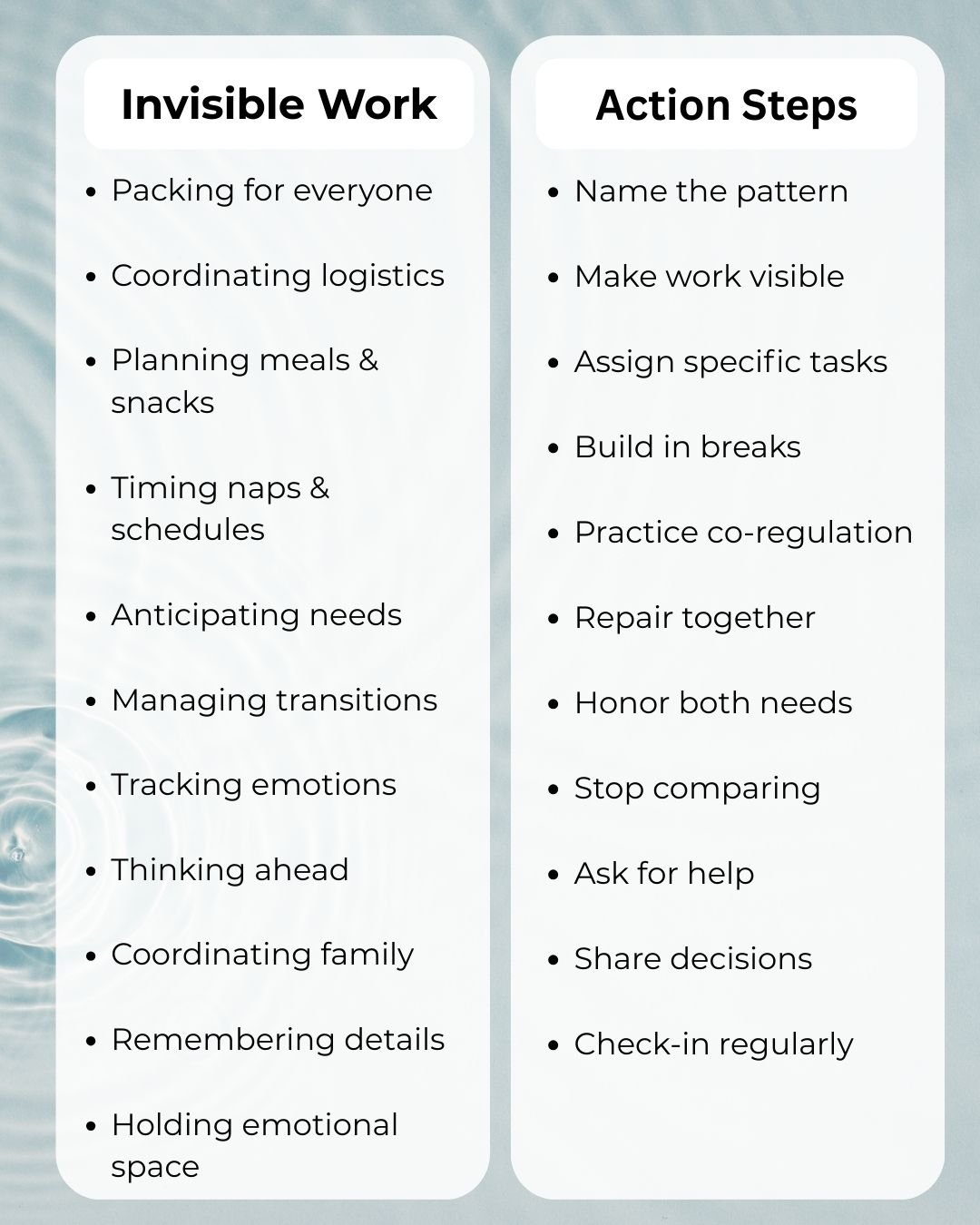

2. Make the Invisible Work Visible

The partner carrying more mental load often doesn't realize how much they're holding until they try to name it. The partner with more available capacity often genuinely doesn't see the work because it's been invisible.

Sit down together and list out every task involved in the upcoming stressor. For a family trip, this might include:

Packing for each family member

Coordinating travel logistics

Planning meals or snacks

Researching activities

Timing naps or managing sleep schedules

Bringing comfort items for kids

Managing transitions and meltdowns

Coordinating with extended family

Thinking three steps ahead about what might go wrong

Tracking everyone's emotional temperature

Navigating family dynamics or expectations

Once it's visible, you can decide together how to distribute the work more equitably.

3. Redistribute Specific Tasks, Not Vague Responsibilities

"Help more" is too broad to be useful. Instead, assign specific, complete tasks to each partner.

Instead of: "Can you help with packing?"

Try: "Can you pack the kids' clothes and toiletries? I'll handle the snacks and entertainment."

Instead of: "Can you help manage the kids during the drive?"

Try: "Can you sit in the back with the kids and handle snacks, entertainment, and emotional regulation? I'll drive and manage navigation."

When tasks have clear ownership, both partners know what they're responsible for. This reduces the invisible work of delegating, reminding, and coordinating.

4. Build in Regulation Breaks for the Partner Carrying More

If you're the partner who typically carries more mental load, you need explicit time to downshift your nervous system during high-stress periods. This isn't optional. It's essential.

This might look like:

Your partner takes the kids for a full morning while you rest, read, or do nothing

You take a walk alone every evening during the trip

You alternate bedtime routines so each parent gets a break on different nights

You communicate clearly when you're at capacity and need your partner to step in fully for a set period of time

These breaks aren't "treats" or bonuses. They're nervous system maintenance that allows you to stay regulated enough to keep showing up.

5. Practice Co-Regulation, Not Expectation Management

One of the most common dynamics I see: the partner with less mental load tries to solve the problem by saying, "Just lower your expectations. It doesn't have to be perfect."

This usually doesn't help. The partner carrying more isn't anxious because they're perfectionistic. They're anxious because they can see all the moving pieces, they know what happens when things fall apart, and they're trying to prevent meltdowns, injuries, or chaos.

Instead of managing expectations, practice co-regulation. The partner with more capacity can say:

"I see that you're stressed. What do you need right now?"

"I'm here. Let's figure this out together."

"I'm going to take over X, Y, and Z for the next hour so you can breathe."

Co-regulation acknowledges the stress without dismissing it. It offers partnership, not platitudes.

6. Repair When Things Go Sideways

You will not get this perfect. There will be moments during high-stress times when one or both of you snap, shut down, or feel resentful. That's normal.

What matters is the repair.

After the moment passes, come back to each other. Name what happened. Acknowledge the stress. Commit to trying something different next time.

Try: "I was really overwhelmed yesterday and I took it out on you. I'm sorry. I think I need us to redistribute some of the planning work before our next trip."

Or: "I didn't realize how much you were holding until you said something. I want to do better at noticing and stepping in without you having to ask."

Repair isn't about erasing the hard moment. It's about reconnecting and moving forward with more awareness.

Ending the Exhaustion Olympics: A Repair Script

When you catch yourselves competing over who's more exhausted, try this repair script:

"We are both red-lined right now. I'm not trying to say my day was harder. I'm trying to say I'm out of gas. Can we stop comparing and figure out how to get us both five minutes of breathing room?"

This script does three things:

Acknowledges both people's reality without comparison

Names the pattern you're stuck in

Redirects toward collaborative problem-solving

The goal isn't to prove who deserves rest more. It's to recognize when the system is overloaded and work together to bring the temperature down for both of you.

A Note on Neurodivergence, Trauma, and Capacity Differences

If one or both partners are neurodivergent (ADHD, autism, sensory processing differences) or navigating trauma or grief, capacity imbalances often intensify during high-stress situations.

A neurodivergent parent might:

Have less available executive function for planning and coordinating during transitions

Experience sensory overwhelm more intensely during travel or disrupted routines

Need more downtime to recover from social or environmental demands

Struggle with flexibility when plans change unexpectedly

A parent processing grief or trauma might:

Experience an "executive function fog" that makes simple decisions feel impossible

Have a more sensitive nervous system that reaches capacity more quickly

Need more explicit structure and predictability to feel safe

Require more recovery time after any kind of activation

These aren't failures. They're differences in how nervous systems process stress and novelty.

If neurodivergence, trauma, or grief is part of your family dynamic, factor it into your planning. The partner with these experiences might need more explicit structure, more recovery time, and more direct communication about what's expected. The other partner might need to carry specific logistical tasks that require more executive function while their partner contributes in ways that align with their current capacity and strengths.

Common Questions About Partnering Through Capacity Differences

1) How do I talk about capacity differences without sounding accusatory?

Use "I" statements and focus on your own nervous system experience rather than criticizing your partner's behavior. This shifts the conversation from blame to collaborative problem-solving.

From my years working with couples, I've found that the most productive conversations start with naming your own experience first. When you lead with "I notice that during school breaks, I feel like my nervous system is maxed out by the end of each day," you're sharing information rather than making accusations. This creates space for curiosity instead of defensiveness.

Try: "I notice that during school breaks, I feel like my nervous system is maxed out by the end of each day. I think it's because I'm holding a lot of the invisible planning and emotional regulation work. Can we talk about how to share that differently?"

This approach acknowledges your partner's good intentions while naming the pattern you want to address together.

2) What if my partner doesn't "believe in" nervous system language or thinks I'm making it too complicated?

You don't need your partner to fully understand polyvagal theory to have a productive conversation. Focus on observable patterns and practical solutions rather than theoretical frameworks.

In my practice, I work with many couples where one partner is drawn to nervous system concepts and the other finds them too abstract or "therapy-speak." What I've learned is that you can achieve the same outcome—redistributing work and reducing resentment—without requiring both partners to speak the same theoretical language.

Try: "I know we might not use the same language around this, but here's what I'm noticing: during vacations, I feel exhausted and resentful by day three, and you seem more relaxed. I think it's because I'm doing a lot of invisible work that you might not realize is happening. Can we list out what needs to happen and figure out how to split it more evenly?"

This grounds the conversation in lived experience, not theory.

3) What if I'm the partner with more capacity and I want to step up, but I genuinely don't know what to do?

Ask directly. Don't wait for your partner to assign tasks or tell you what to do in the moment. The most helpful thing you can do is initiate the conversation about what's invisible to you.

I often work with partners who have good intentions but genuinely can't see the mental load because it's never been on their radar. The fact that you're asking this question shows you care and want to contribute more equitably. That willingness is the foundation for change.

Try: "I know I tend to have more bandwidth during stressful times, and I want to share the load more equitably. Can you help me understand what work you're holding that I'm not seeing? Let's make a list together so I know what to take on."

This approach shows genuine curiosity and shared responsibility for solving the problem.

4) What if we've tried redistributing tasks and it still feels uneven?

Capacity differences aren't just about tasks. They're also about emotional labor, decision-making, and mental tracking. Even if you're splitting the visible work 50/50, one partner might still be doing more of the invisible work of coordinating, anticipating, and holding everyone's emotions.

Check in on:

Who's thinking ahead and problem-solving?

Who's making the majority of decisions?

Who's managing everyone's emotional state?

Who's tracking what needs to happen next?

These are the areas where imbalances often persist even when task lists are divided evenly.

5) What if my partner thinks I'm "overreacting" or being "too sensitive" about needing breaks or support?

This is not a personal failure, it is a nervous system mismatch. Your partner likely has more capacity and genuinely doesn't feel the same level of overwhelm. That doesn't mean your experience isn't valid it means you have different thresholds for what feels manageable.

From years of working with couples navigating this dynamic, I've found that the partner with more available capacity often can't feel what the other is experiencing. They're not being dismissive on purpose; they literally don't have the same physiological response to the same situation. But that doesn't make your overwhelm less real or less important.

Try: "I hear that this feels manageable to you, and I'm glad. For me, my body is telling me I'm at capacity. I'm not overreacting. I'm listening to what my nervous system needs to stay regulated. I need us to take that seriously, even if it doesn't match your experience."6) How do I know if this is a capacity issue or something deeper in our relationship?

If redistributing tasks, building in breaks, and practicing co-regulation helps, it's likely a capacity issue that you can work through together.

If your partner consistently dismisses your experience, refuses to engage in problem-solving, or expects you to manage everything while they remain passive, that's a deeper relational issue that might benefit from couples therapy.

6) How do I know if this is a capacity issue or something deeper in our relationship?

If redistributing tasks, building in breaks, and practicing co-regulation helps, it's likely a capacity issue that you can work through together. If your partner consistently dismisses your experience, refuses to engage in problem-solving, or expects you to manage everything while they remain passive, that's a deeper relational issue that might benefit from couples therapy.

In my practice, I look for willingness as the key indicator. Partners who have genuine capacity differences are usually willing to problem-solve once they understand what's happening. They might not see the invisible work initially, but when it's made visible, they're willing to step up. Partners with deeper relational issues resist taking responsibility even when the imbalance is clearly named.

Pay attention to whether your partner responds with curiosity and effort or with defensiveness and dismissal. That tells you whether you're dealing with a capacity gap or a relationship pattern. Many times poor communication in a relationship about capacity, leads to deeper concerns.

7) What if I'm the partner with more capacity and I'm starting to feel resentful that I "have to" step up more?

That resentment is worth exploring. Sometimes it's about not wanting to do invisible work that doesn't come naturally. Sometimes it's about feeling like you're always accommodating your partner's needs without reciprocity.

I work with many couples where the partner with more capacity initially steps up willingly but then starts to feel taken advantage of. This is a sign that something about the dynamic doesn't feel fair or sustainable. Your resentment is valid information.

Ask yourself:

Am I stepping up in ways that feel genuinely generous, or am I doing it out of obligation and building resentment?

Do I feel like my needs matter equally in this partnership?

Is there reciprocity in other areas of our relationship, even if capacity differences mean I carry more during high-stress times?

If the answer to these questions reveals ongoing imbalance, this is a conversation worth having with your partner or in therapy. Partnership requires both people feeling valued and supported, not just during crisis times.

8) What if we're both maxed out and nobody has capacity to spare?

This is burnout. When both partners are consistently operating at or beyond capacity, something has to give. The system is overloaded and redistribution alone won't solve it—you need to reduce overall demands.

I see this pattern frequently with families juggling multiple young children, demanding careers, aging parents, or major life transitions. Both partners are running on empty. In these situations, trying to "optimize" who does what misses the point. The total load is unsustainable for two people, period.

Consider:

Can you simplify the stressor? (shorter trip, fewer activities, less ambitious plans)

Can you ask for outside support? (family, friends, paid help)

Can you build in more recovery time before and after the stressor?

Do you need to reassess your overall life demands and make bigger changes to protect your family's collective nervous system capacity?

Sometimes the answer isn't better redistribution. It's pulling back from the demands altogether.

Moving Forward: Small Shifts That Compound

Partnering through capacity differences isn't about fixing the problem once and never dealing with it again. It's an ongoing conversation and recalibration, especially as your family changes, stressors shift, and life circumstances evolve.

What makes the biggest difference isn't perfection. It's willingness. Willingness to see each other's experience. Willingness to name what's hard. Willingness to try something different. Willingness to repair when things fall apart.

From my years working with couples navigating parental burnout and capacity imbalances, the partnerships that thrive aren't the ones where both partners have equal capacity all the time. They're the partnerships where both people feel seen, both people's needs matter, and both people are actively working to share the invisible work of holding a family together.

That's the goal. Not equal capacity. Not perfect distribution. Just partnership that feels sustainable for both of you.

Free Download: The Pre-Transition Nervous System Check-In

Most partner conflict during vacations happens because we haven't checked in on our individual capacities before the stressor hits. I've created a simple tool to help you and your partner identify your regulation needs, sensory sensitivities, and non-negotiables before your next big transition.

Download the Nervous System Check-In Here

About the Author

Lisa Brooking is a Registered Clinical Counsellor (RCC) and Occupational Therapist (OTR/L) in Vancouver, BC, specializing in nervous system regulation, parental burnout, and neurodivergent support. With over 14 years of clinical experience, she helps overwhelmed parents and neurodivergent adults rebuild regulation capacity so daily life doesn't feel this hard. Her approach integrates polyvagal theory, sensory processing, and attachment-based therapy to support sustainable change.

If you're ready to move from resentment to sustainable partnership, I'd be honored to support you. Book a free consultation to discuss how regulation-focused therapy can help your family.